Submission to the Commission of Inquiry into the Tasmanian Government’s Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Settings - July, 2021

Engender Equality calls for an adequate understanding of the role that organisational culture plays in enabling child sexual abuse in institutional settings and proposes that hierarchical allocation of power within bureaucratic systems reduces the opportunities for individual accountability, with the result of diminished transparency. Our submission has been researched and written by Dr Morag MacSween and is informed by over three decades of experience as a service provider, advocacy organisation and strategic partner in the Tasmanian family and sexual violence sectors.

Sexual assault, stigma and suicidality

Mercury Newspaper | July 2021

Despite increased attention given to suicide prevention, we see little if no reduction in suicide statistics. Coronial inquests look at the circumstances around individual cases. The new Royal Commission into veteran suicides will look into “military life” but it is not leading with the impact of trauma as a causal factor. A common response to the high rates of suicide and suicide attempts among sexual assault survivors is to lament their ‘lost battle’ with stress, anxiety and depression.

With an increase in disclosures of sexual assaults in Australia, comes a growing awareness of the length of time it takes for a person to disclose and the correlations between the experience of sexual assault and suicide.

If we unpack this response for a moment, the idea that sexual assault flicks a mental health switch that results in a suicide, we see that we risk reducing the context of a person’s death to a poorly managed individual response to a triggering event. From the perspective of specialist support services, there is undoubtedly much more to the story of sexual assault and suicidality than poorly managed mental health.

While mental wellbeing is acutely relevant to suicidality, social conditions (therefore conditions that can be changed) are also inevitably present within the experience of suicide. In particular, the experience of stigma is recognised as being significant for people experiencing suicidal ideation.

The high rates of suicide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and for LGBTI+ community members tell us that there are shared experiences of stigma, mixed with social exclusion and discrimination that increase the risk of suicide. When these elements overlap with normal human experiences of anxiety and stress, the conditions are in place for increased suicide attempts and higher fatal suicide statistics.

Childhood sexual assault is one of the most stigmatising experiences a person can endure. And while fear of social stigmatisation prevents many sexual assault survivors from accessing support or reporting their experience, the coinciding internalised stigma is a burden that results in childhood sexual assault survivors taking on average 24 years to disclose the crime, if they disclose at all.

The pervasive burden of stigma is described well by a survivor who declared, “even my cat stigmatises me.“

Even without disclosing the experience of abuse, survivors often feel deeply humiliated, disgraced and ashamed. They rightly fear being blamed by others and most will blame themselves. They can be left bearing such responsibility for what they have endured that a disclosure feels almost like an admission. As one survivor shared, “Internalised stigma feels like wearing a neon sign that loudly declares your experience even when you’ve never told another person.“

There are many reasons for this, including the fact that in normal childhood development children blame themselves for traumatic things that happen. Further, the assault itself may have been delivered as an act of punishment: “if you weren’t naughty I wouldn’t have to do this.” These conditions are compounded by Draconian ideas about sex that suggest many sexual acts are sinful and the result of a personal failing.

Research shows survivors from already marginalised populations are more likely to be disbelieved and receive a negative response when they seek help compared with the general population. For marginalised people, the stigma intensifies.

When we think about the high rates of suicidality amongst people who have experienced sexual assault, we must think about the social context of accountability, responsibility and justice in which they lived. If the assault is constructed as being the fault of the victim, this becomes the experience that they have to live with.

When we think about the suicide of sexual assault victims, we need to acknowledge the conditions in which they lived. People who have experienced sexual assault don’t end their life because of a failed attempt to manage their mental health, but because the conditions of their existence held them responsible for the trauma and very likely afforded a level of protection to the perpetrator.

The antidote to this situation is to believe survivors, regardless of their social circumstances. We need to elevate survivors to the position of expert, regarding both their lived experience and the response they need to survive it. Our service and justice responses must be designed to provide comfort and restore dignity in every way. For as long as this is not occurring, we will be limiting the opportunities for accountability in the perpetration of child sexual assault.

Another necessary correction is to expect and model transparency at all times. Understanding that sexual assault always occurs when there is an imbalance of power means calls for the experience of power to be scrutinised with no exceptions – at home, in the workplace, in schools and elsewhere. For those with power over others and in positions of power, the need to understand the responsible use of power is essential. Values, language and behaviours that blame, minimise, or disregard sexual assault need to be exposed, challenged and eradicated.

When people who have experienced sexual assault end their lives, we must acknowledge that the cause of their death lies in the trauma they have been subjected to in a society that has not only failed to protect, but also failed to respond with due compassion and accountability.

Alina Thomas is the CEO of Tasmania family violence service, Engender Equality. In her work, she calls for a social examination of gendered issues. Alina is a white woman, living on the stolen lands of the palawa people.

If you would like to talk to someone about your experience please call 1800 RESPECT on 1800 737 732.

Tasmanian advocates say disability sexual violence rates underrepresented

By Brinley Duggan

Posted to The Examner online July 19 2021 – 11:18am

The reality of how many people with a disability are survivors of sexual violence is grossly underreported, according to advocates and victim-survivors.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics the rates fluctuates around 30 per cent, while data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates the number to be close to 60 per cent.

Whichever way it is looked at, the number is “mind blowingly high” and a reflection of both the system and social supports failing says North-West Tasmanian disability advocate Tess Moodie.

“It’s so difficult when we start talking stats because it’s such a largely underreported area for multiple reasons.”

“We know it’s higher than the research shows.”

Tess Moodie is a victim-survivor of sexual violence and has multiple diagnosed forms of disability, including Ehlers-Danlos Syndrom and being on the autism spectrum.

“I wasn’t diagnosed as autistic until I was 41,” they said.

“As a teenager I didn’t have a great understanding of social cues and risk and which people were safe and which people weren’t. This made me more at risk of predatory behaviour from older men.”

Tess Moodie is determined to use their experience to power them in their advocacy, help raise awareness and work to reduce violence against women with disability.

“We’re only vulnerable because society makes us that way. Society doesn’t protect us and safeguard us when it should.”

They said without support structures people with disability were often unable to identify or report sexual assault or even communicate that something that happened to them was sexual assault.

Lacking educational frameworks, accessibility to support services and targeted prevention responses were to blame, they said, and the fact the person caring for them was often the one perpetrating the assault further complicated the ability to report.

We’re only vulnerable because society makes us that way. Society doesn’t protect us and safeguard us when it should.

Tess Moodie

Tasmanian disabled woman, victim-survivor and advocate Sara Pensalfini echoed Tess Moodie’s comments.

Ms Pensalfini’s childhood was marred by prolonged sexual abuse from a young age.

Like Tess Moodie, Ms Pensalfini has turned her experience into relational advocacy. Ms Pensalfini, like Tess Moodie, exudes the sense that enough is enough when it comes to sexual violence being perpetrated against women with disability.

“We talk about vulnerability but the shift has to actually go to why are we more vulnerable?” she said.

“We’re preyed upon. Vulnerable people are preyed upon by predators.”

“First and foremost we need to spend more time, money and focus on early intervention to stop predatory behaviour.”

Launceston and North-West based sexual assault support service Laurel House is working to help people with a disability who are survivors of sexual violence

Disability project officer Kim Atkins has been working within the field for years and is currently developing a program at Laurel House aimed at building capacity for health providers, allied health professionals and disability service providers to improve their ability to respond to disclosures of sexual assault.

Laurel House disability project officer Kim Atkins. Picture: Craig GeorgeShe said the need to hone in on the reality of sexual assault in the disability community was imperative.

“Up to 90 per cent of people living with disability may have experienced sexual assault at some time in their life,” she said.

“It’s an absolutely staggering problem. And the vast majority of disability health providers that work in the sector aren’t aware that the rates are so high.”

Ms Atkins said the issue of sexual violence perpetrated against women with disability had been continually pushed to the back of the mind, and the line, and only now was its reality being remotely understood.

“As horrible as it sounds, society has a pecking order and people with disability have been largely voiceless,” she said.

“Then if you are a person with a disability there are additional barriers to disclosing sexual assault. There’s a range of barriers for people with disability.”

Ms Pensalfini and Tess Moodie said the community affected by the high rates of sexual violence were fully aware of why it had happened and how it was able to continue.

They said the lack of social structures had been a perpetuating problem where victim-survivors were rendered voiceless, and predators were empowered.

Ms Pensalfini was defiant in drawing her line in the sand, enabled by programs like the one Ms Atkins is powering and the voices of people with a similar voice like Tess Moodie.

“We’re all human beings. The idea of equity should be that we all have a right to not be sexually abused,” she said.

“Some people have an easy way of communicating what’s going on in their lives and it’s our responsibility as a society to put these things in place to make sure those people have even more opportunities to communicate in whatever way they need to as to what is going on.”

“There needs to be higher amounts of service in these areas, and that’s just not happening.”

Upholding the presumption of innocence does not preclude believing victims

Published in The Mercury, 19 May 2021

With distressing regularity, women in Australia are disclosing their experiences of sexual and interpersonal abuse at the hands of male politicians and men in senior public office. As we come to grips with the pervasiveness of a culture of sexual impunity that, it seems, reaches even the highest echelons of Parliament, we are witnessing another unsettling trend: the failure of our leaders to condemn the abuse in question.

The default explanation is all too familiar: the individual against whom the allegations have been made has denied any wrongdoing; they are entitled to the presumption of innocence; it’s a legal matter and no comment can be made.

And yet, we know the prevalence of violence against women is abhorrently high in Australia. We also know that sexual and interpersonal crimes often go unreported and are even less frequently prosecuted in the courts. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, fewer than one in five women have reported their most recent sexual assault to police.

For many women and children who have been abused, disclosing the experience comes at an enormous personal cost. Their integrity is doubted, their mental health is called into question; at some level we ask, “What could she have done to prevent it?”. If a case does reach court, the ensuing stress will cause a lasting impact on the victim-survivor. For many, the justice process becomes the defining story that shapes the rest of their life.

The barriers to reporting sexual crimes are only heightened when we insist that the law itself prevents us from condemning acts of abuse and expressing support for victim-survivors. The presumption of innocence should never be positioned in opposition to the fundamental principle of listening to, believing, and supporting people who have experienced abuse. While we continue to feel that we must do one or the other we are missing a critical opportunity to address broader cultural values that condone violence against women.

When our leaders and others in positions of influence feel compelled to ‘take a side’, they immediately declare that one account of events deserves to be upheld, inevitably suggesting that the other account should be called into question.

If we unpack this automatic positioning of a disclosure of abuse in opposition to the principle of law, we understand the reluctance of victim-survivors to report their experience. Each time a public figure refrains from commenting on a disclosure of interpersonal abuse they reinforce the common myth that women fabricate sexual crimes. Furthermore, they demonstrate that the wellbeing and discretion of people who use abuse will be protected by their contemporaries.

Supporting survivors alongside upholding the principle of law isn’t only possible, it is essential. The contemporary spotlight on gender-based violence brings with it an expectation that our political and cultural leaders will demonstrate compassion and respect towards all victims of violence and abuse.

Allegations of abuse will continue to arise and the response must be to offer an expression of gravity to the allegation. Leadership must deliver a statement of empathy and extend dignity to the people who have potentially exposed the misconduct.

The challenge for this decade is to shift the complacency that tolerates gender-based violence. The insidious belief that violence against women in an unfortunate but inevitable ill must be addressed at every opportunity. Our goal must be to bring to light the everyday behaviours that perpetuate this complacency. Talking about abuse should not create more harm than the abuse itself.

As for the alleged behaviour, whether it has occurred or not, its very possibility should be condemned by our leaders. Condemning an act or indeed a culture of abuse is entirely possible without defaming individuals.

Improving the way our leaders respond to accusations, against themselves and their peers, will invite a new level of accountability, new standards of behaviour and play a key role in the culture change that is so vital to reducing sexual violence in Australia. The time to develop this maturity is now.

Authors:

Alina Thomas, CEO Engender Equality

Elinor Heard, Policy & Communications Officer Engender Equality.

Submission to the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability - March, 2021

Developed in conjunction with Dr Morag MacSween, our submission to the Royal Commission focuses on the experience of people with disability in relation to violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation caused by family and relationship violence. This intersection is too often invisible in public debate.

Speaking out to end violence against women

Friday 1st February 2019

Speaking out to end violence against women

- Approximately one quarter of women in Australia have experienced at least one incident of violence by an intimate partner.

- Australian women are most likely to experience physical and sexual violence in their home, at the hands of a former or current male partner.

- On average, one woman a week is killed by her intimate partner.

(Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, 2018)

Despite these statistics, the voices of women who have experienced violence and abuse are often missing from the media.

In partnership with Our Watch, Tasmanian family violence service Engender Equality is facilitating a media advisory training program called Advocates for Change.

“The Advocates for Change program offers training to Tasmanian survivors of family violence to safely tell their story. It aims to improve the reporting of family violence in Tasmania and address the stigma that family violence victim’s experience,” explains Alina Thomas CEO of Engender Equality.

The Tasmanian Government is a member of Our Watch, the national organisation set up to drive change in the culture that leads to violence against women. Our Watch focuses on strengthening primary prevention messages, highlighting the connections between gender inequality and violence against women.

“Engender is very excited to be running this program with Our Watch. Over the years we have had many women want to share their experience to support other people who have experienced family violence and this program will give the resources to make that happen in a safe way,” Ms Thomas explained.

Training is free for participants and will be conducted in Hobart and Launceston.

Expression of interest remain open until Friday 8 February 2019 and can be completed online via this link: https://form.jotform.co/83378373663872

For all media enquiries please contact:

Alina Thomas

Tasmanian women’s organisations support birth certificate changes

Wednesday 7th November 2018

Speaking up for Tasmania’s Women

In recent debate regarding proposed amendments to the Justice and Related Legislation (Marriage Amendments) Bill 2018, incorrect statements have been given a platform by groups such as Women Speak Tasmania (‘WST’).

WST say the safety of women’s services is at risk if transgender women are allowed access.

Further, WST claim to speak for the concerns of the broader Tasmanian community in this – presumably for Tasmanian women.

We are a group of women’s specialist services. WST did not consult our representatives before making these statements and they do not represent the views of our organisations, staff, Boards of Governance or membership.

It is our position that transgender women are women and they are welcome at our services.

As key organisations representing women’s voices in Tasmania, our service policies and advocacy positions are developed through regular processes of discussion and consultation. We have not been informed of any consultation process by Women Speak Tasmania through which their policies were developed.

We can say with certainty that they do not represent the large number of women associated with our organisations. They do not speak for us.

The proposed amendments are narrow in scope, relating to two discrete issues: the removal of sex markers on birth certificates; and the removal of the requirement for transgender people to undergo sex reassignment surgery in order to obtain documents that properly reflect their true gender. To assert that the reforms represent anything more than this is wrong.

Women Speak Tasmania hold the position that transgender women are not women and oppose the amendments on this basis. This is unjust and prejudicial.

WST also argue that transgender women pose a threat to women’s safe spaces.

There is no research or service experience to suggest that men who seek to harm women change their gender or masquerade as transgender women in order to do so.

Acknowledging in law the human rights of transgender people does not reduce the human rights enjoyed by non-transgender people. Protecting women’s rights and supporting transgender people are not mutually exclusive.

Through our collective experience of providing legal, health, domestic violence and housing services to women, we are already successfully supporting transgender women who, it should be noted, are often themselves victims of violence and targeted by people who use abusive behaviour.

Arguments such as those promulgated by WST only result in greater danger, including physical assaults to transgender women, non-binary individuals, and women who do not conform to stereotypes of femininity. These attitudes also stand as barriers to gender diverse people accessing services and as such, they remain at greater risk to violence and abuse.

For the vast majority of the population the proposed amendments will have no apparent practical impact. But for those in the transgender, gender diverse and intersex community the impact is profound.

The amendments do very little, beyond making life significantly easier for a small group of people. To the extent that WST have an issue with that, it is clearly an ideological one and in its effect it is discriminatory.

Our organisations have always been a safe and welcoming place for all women and they remain so.

For further media enquiries please contact:

Alina Thomas

Chief Executive Officer

Susan Fahey

Women’s Legal Service Engender Equality

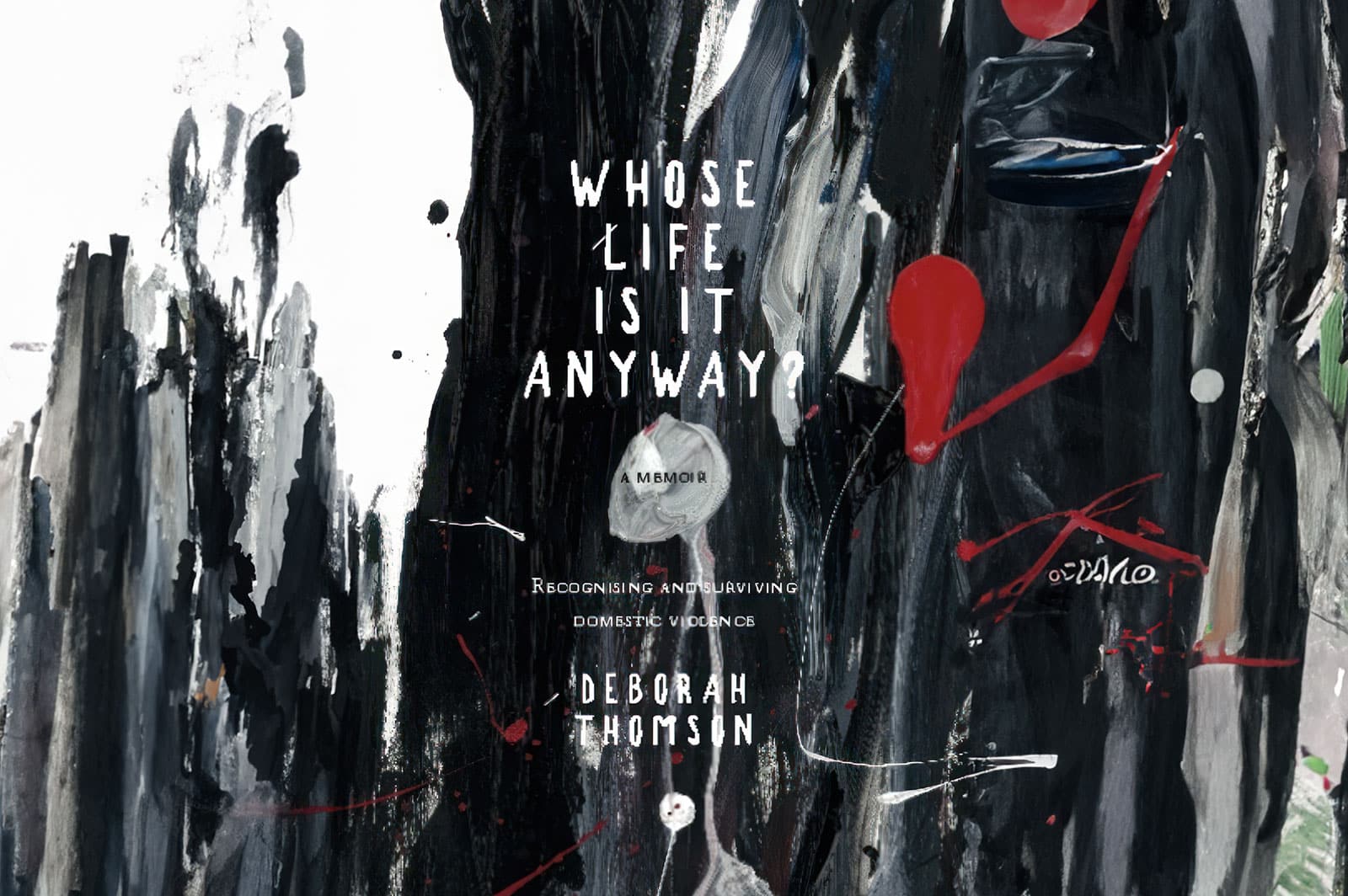

Local author tells personal story to support family violence victims (book launch)

Monday, 16th April 2018

Local author tells personal story to support family violence victims (book launch)

Deborah Thomson found the peaceful life she always wanted in Chasm Creek, on the North Coast of Tasmania, but it took her a long time to get there. Deborah Thomson has written a book about what happened when her life was changed irrevocably by an abusive partner, a relationship which she endured for 17 years.

Whose Life is it Anyway? Recognising and Surviving Domestic Violence published by Brolga Publishing, aims to support people being impacted by abusive partners. “I have written this book to help others in similar situations to leave early in their relationship, before they too suffer debilitating trauma,” stated Deborah Thomson author of the new book. “Since leaving I have come to realise how debilitating trauma is when associated with staying in a long-term violent partnership. Lived experience has shown me that such trauma can take half a lifetime to resolve,” explains Ms Thomson.

Alina Thomas, CEO of Family Violence service SHE, says that Deborah’s experience is not uncommon. “Trauma is an inevitable consequence of long term abusive relationships. We see hundreds of women, every year in Tasmania who are left with physical and emotional symptoms of trauma due to ongoing abuse in relationships.”

The courage of women who have survived Family Violence can give hope to other people experiencing family violence as well as be a source of inspiration to the broader community. Family Violence advocate Rosie Batty changed the way that Australia responded to family violence and our local advocates say there is still a lot that needs to happen. As Author Deb Thomson explains, “we need to do whatever we can to keep the issue of DV in the public’s vision while simultaneously supporting victims in whatever way possible”.

Alina Thomas believes there needs to be a greater investment in primary prevention and early intervention. “In Tasmania we are very focused on a tertiary response, what the police and the courts do after the violence has occurred. But if we are going to see a reduction in the family violence epidemic we need to be investing in programs that target the problem before it escalates to this point,” stated Ms Thomas.

Deborah Thomson’s book Whose life is it Anyway will be launched by Her Excellency Professor the Honourable Kate Warner AC at Fullers Bookshop on Wednesday 18th April at 5.30pm.

For photos, interviews and more information please contact:

Deborah Thomson, Author

Alina Thomas, CEO SHE

Improving services for mental health and family violence

Monday 14th November, 2016

Improving services for mental health and family violence

Tasmanian Family Violence Service, SHE (Support, Help and Empowerment), has today released a Family Violence toolkit for mental health professionals. The toolkit provides a go to guide on the basics of working with people who are experiencing family violence.

This important new resource, being launched by Robin Banks, the Equal Opportunity Commissioner of Tasmania, also supports family violence training SHE has delivered to the mental health sector.

“With the growing awareness of the causes and prevalence of family violence in Tasmania, comes a responsibility for community services to be able to work effectively with those who are being impacted,” explained, Mental Health Council of Tasmania CEO, Connie Digolis.

There is a significant body of research that links a bi-directional causal relationship between exposure to family violence and persistent mental health challenges. However, family violence is often a hidden problem among people seeking support for their mental health issues[i].

SHE Executive Officer, Alina Thomas states that, “if women are seeking help with symptoms of mental illness it can be very likely that family violence is an underlying issue. This resource will be the first of its kind to bring together the specialist practice of family violence intervention and the important work that is being done in the mental health sector.”

Under a grant received from the Partners in Recovery Tasmania, SHE has also designed and delivered a Champions Program to upskill those working in the mental health field to become more confident in responding to people experiencing mental health issues and family violence. The program has been an outstanding success with 12 people from across the State graduating from the intensive training today.

“Recognising and responding effectively to people who have experienced family violence requires specialist knowledge of the dynamics and conditions that they have experienced” explained Alina Thomas, Executive Officer of SHE.

The SHE program has provided important insight and understanding to the complex issue’s surrounding mental health and family violence. It is anticipated that many people, both workers and the community they support will benefit from the new toolkit and training.

(If you need help, please call Family Violence Counselling and Support Services on 1800 608 122 or SHE on 03 6278 9090)

[i] TREVILLION, K., ORAM, S., FEDER, G., & HOWARD, L. M. (2012). Experiences of Domestic Violence and Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, PLoS ONE, 7(12)

Women want women’s services – family violence victims speak out

Women want women’s services – family violence victims speak out

Tasmanian Domestic Violence Service, SHE (Support, Help and Empowerment), has released new research on the needs of women who have experienced domestic violence in an attempt to better inform services across the State.

The Hodgman Government is in the process of releasing over 5.5 million dollars to improve service delivery to people in, or leaving, violent and abuse relationships. “With many family violence services experiencing unparalleled high levels of demand, it is commendable that the Liberal Government is showing unprecedented support for domestic violence service in Tasmania”, declared Alina Thomas, Executive Officer of SHE.

The research conducted on behalf of SHE, investigates the experience of women accessing services to address the impacts of family violence. “What we found is that, while each woman had a unique experience leading them to needing help, the service needs were surprisingly similar….we found that empowerment was identified as the most important priority for women. Empowerment is about being heard and believed, regaining autonomy and realising your choices,” explained key researcher Sarah Van Est.

With the primary drivers of family violence now widely identified as gender inequality and rigid gender roles, women-orientated services that draw on a feminist framework for service delivery have been shown to yield the best outcome for family violence victims. “Women need to know that their safety is paramount. They want to be heard and they want to be believed. For women who have experienced repeated abuse and made to feel like they are responsible, to blame or deserve the abuse that has been inflicted up them, empowerment is a very powerful and healing experience”. Ms Thomas states.

One of the research participants shared, “the biggest thing for me, it that my counsellor was the only person ever, in all my contact with services, who never asked me to consider things from his point of view and didn’t ever make me doubt that it wasn’t bad, or significant, or life affecting”.

SHE is hoping that the research will continue to guide the development of family violence services across the State to ensure best practice and value for money.

The SHE research will be launched today (on the 16th March) by her Excellency Professor the Honourable Kate Warner AM, at Government House, Hobart.